Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters (PICCs) (Part three)

Best practice in PICC use: Troubleshooting common complications

This article is part of a series about PICCs.

Introduction

The last article in this series discussed methods to reduce the risk of complications in PICCs. This final article will focus on how to troubleshoot some of the most common complications associated with PICCs if they do occur.

:

- Occlusion

- Phlebitis

- Infection

- Dislodgement

- Catheter fracture

Occlusion

This first section will focus on PICC occlusions. A patent PICC is defined as one that flushes and aspirates freely and without resistance. Catheters that are not fully patent should be investigated.

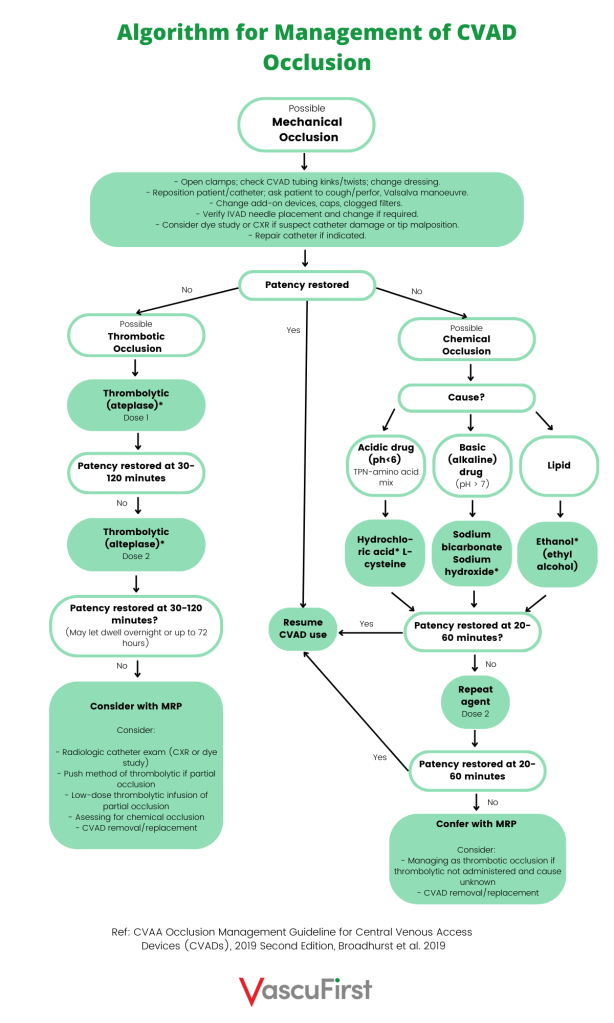

Types of PICC occlusion

Catheter occlusions are categorised as either total, partial or persistent withdrawal. They are the result of either a mechanical or chemical or thrombotic issues. Wherever possible, if the catheter is still required for treatment, attempts should be made to restore catheter patency.

Signs of loss of PICC patency

If you come across any of these issues when working with a PICC, you should take action to investigate and resolve the issue:

- Frequent alarming of infusion pumps

- Incomplete or delayed infusion completion

- Inability to infuse fluids

- Swelling or leakage at insertion site

- Sluggish flow

- Inability to aspirate blood

- Slow or sluggish blood return

These issues are associated with early or late device occlusion. The following section will describe the signs of loss of patency, types of occlusion and actions to take in each scenario.

Inability to aspirate blood

Prior to using a PICC, it should always be checked for patency. This is done by gently drawing back on the syringe and confirming of a swift blood aspirate. If blood aspiration is not possible, or is sluggish, a small amount of saline can be instilled (Denton, 2016; Gorski, 2021). The use of saline at this stage will not cause the patient harm. Gorski et al. (2021) also suggests that a small barrel syringe can be used to attempt blood aspirate. The use of a small syringe will exert less negative pressure and might improve the success.

Persistent withdrawal occlusion (PWO) / Partial occlusion: This is defined as the ability to flush freely but an inability to aspirate. This can be caused by fibrin building up along the PICC. This can lead to a fibrin sheath, flap or tail. It can also be the result of the catheter tip position being positioned against a vein wall. Do not administer vesicant medications if PWO is present. This is to reduce the risk of extravasation.

Actions

Action one: Firstly, ask patient to change the position of their arm, breathe deeply, cough. This should move the catheter tip off the vein wall of the vein if this is causing the problem. Attempt to flush gently with normal saline.

Action two: If this is unsuccessful, thrombotic occlusion should be suspected (Gorski, 2021). Treatment with a thrombotic agent such as urokinase or tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) (alteplase) should be performed. Stop all infusions prior to administering thrombolytic agents. Always discuss thrombolysis treatment with a pharmacist. Always follow your institutions policies and procedures and use thrombotic agents in line with the directions for use provided by the manufacturer. The treatment can be repeated a second time if necessary. Thrombolytic agents can also be administered via an infusion. Remember that every lumen should be treated even if occlusion is only evident in one. Aspirate the thrombolytic agent following the appropriate dwell time. Discard. The catheter should then be flushed and patency assessed.

Action three: Consider requesting a chest x-ray.

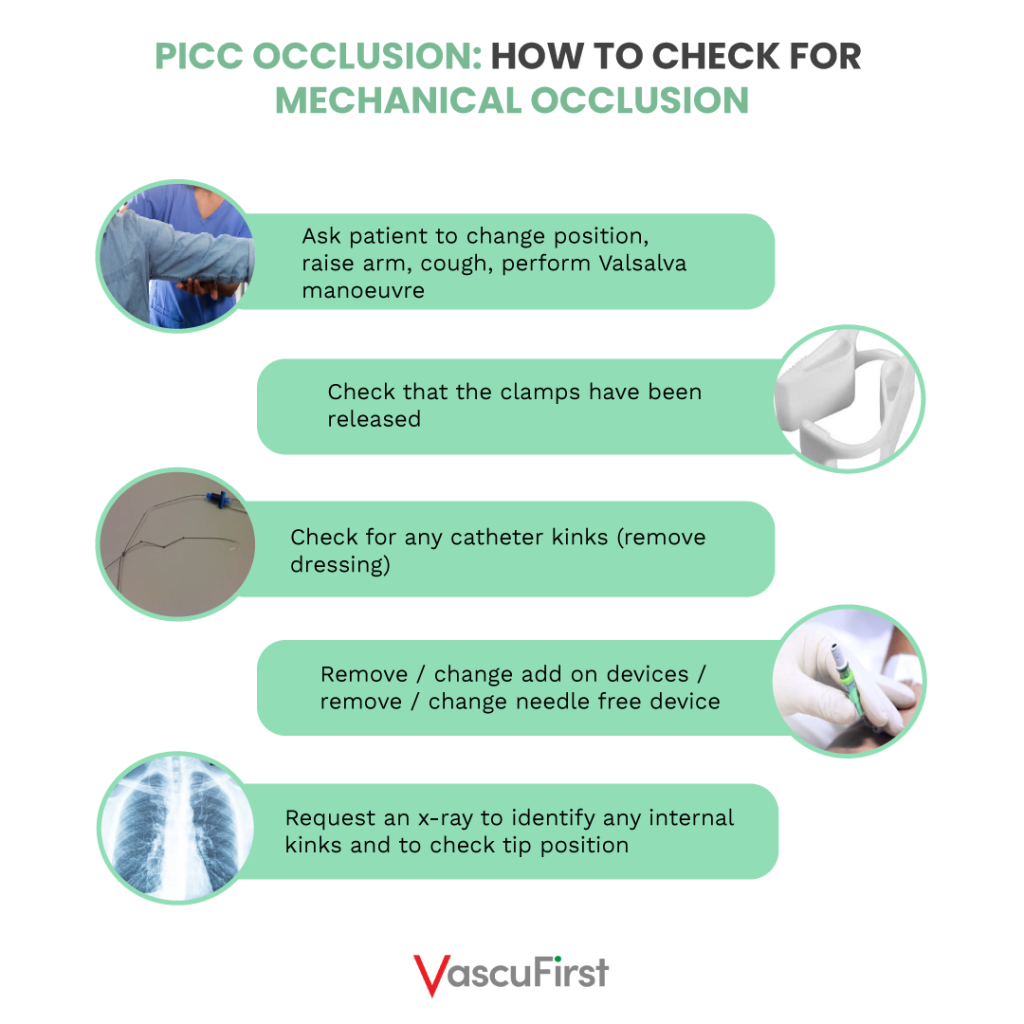

Total occlusion

A total occlusion is defined as the inability to flush and aspirate the PICC. This complication could be the result of a mechanical issue. Clamps could still be activate, the catheter could be twisted or kinked. Poor tip positioning could have left the tip of the catheter sitting against the wall of the vein. If not mechanical occlusion, chemical occlusion should be considered.

Actions

Action one: Check that the clamps have been released.

Action two: Reposition patient. Ask them to raise their arm whilst attempting to aspirate the catheter. Asking them to cough, or to perform the Valsalva manoeuvre. This might result in the catheter tip being in a better position and resolve the problem.

Action three: Check if there were any kinks in the catheter. Remember to remove and to check under the dressing. This issue should be resolved according.

Action four: The needle free device or other add on devices could also be the cause of catheter occlusion. Therefore, part of your investigation for a total occlusion would be to change the needle free device, caps and filters.

Action five: Consider performing an x-ray to check for internal kinks in the PICC (Broadhurst et al,. 2019).

Action six: For a total occlusion, a thrombolytic agent can be administered using a 3-way stopcock. Follow hospital policy and procedure and manufacturer instructions.

NEVER ATTEMPT TO UNBLOCK A PICC UNDER PRESSURE: THERE’S A RISK OF CATHETER FRACTURE.

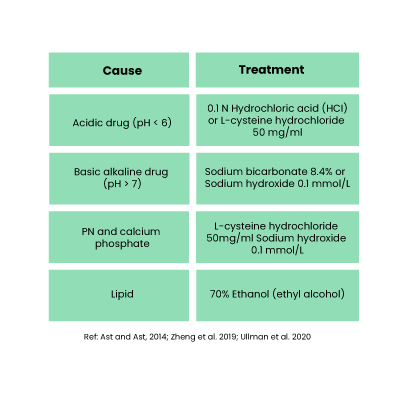

Chemical occlusion

Chemical occlusion can cause total occlusion. This can occur when a PICC has not been adequately flushed. This can result in the build-up of lipid within the catheter lumen (Broadhurst et al. 2020). Additionally, when two incompatible medications are administered through the device, precipitation or crystallisation can occur causing complete occlusion of the device. An attempt should be made to reverse a chemical occlusion.

Actions

Action one: The priming volume of the PICC needs to be considered

Action two: Administer the relevant catheter clearance agent and allow to dwell for 20 to 60 mins

Action three: This can be repeated if necessary

Action four: Following appropriate dwell time, the catheter clearance agent should be aspirated and discarded

Action five: The PICC should then be aspirated and flushed to check if patency has been restored (Broadhurst, 2020; Gorski. 2021)

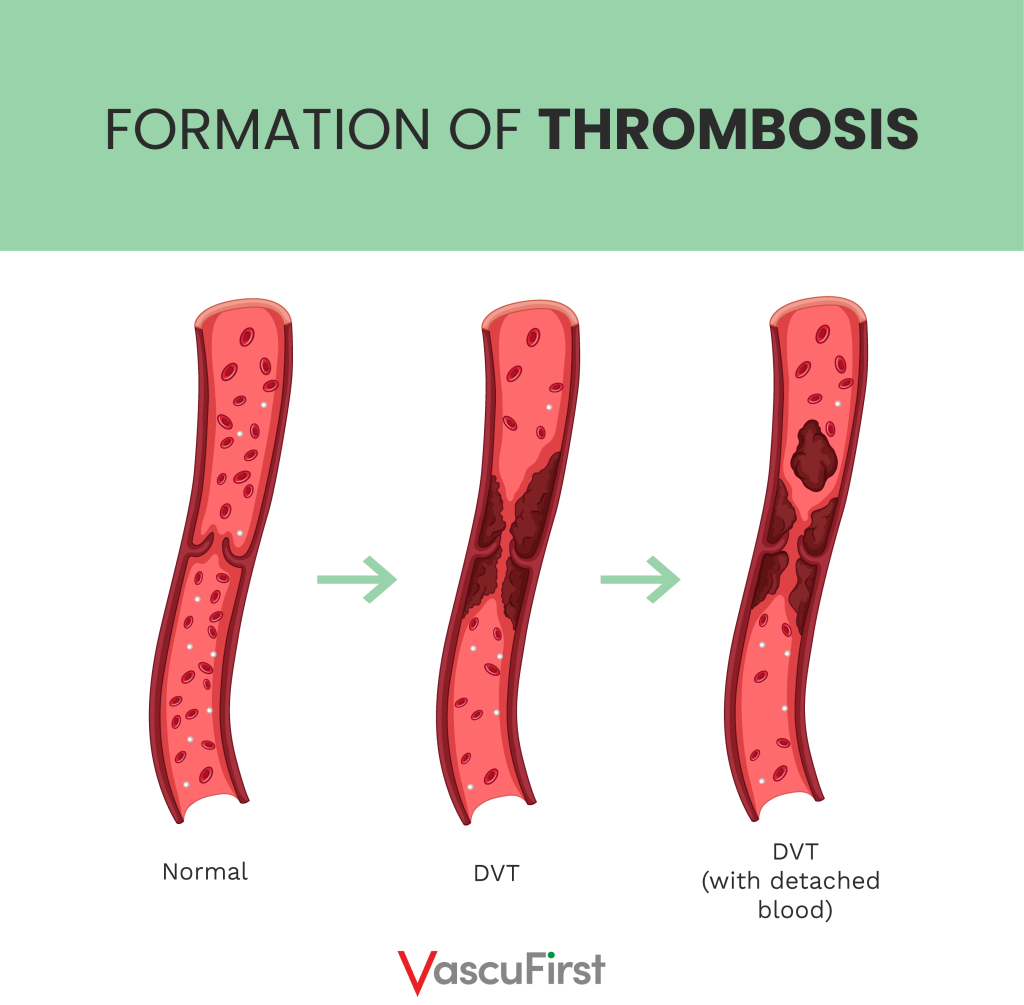

Thrombotic occlusion

Thrombotic occlusion should be considered after ruling out mechanical or chemical occlusion. This is caused by a blood clot within the vein. It should be noted that the majority of thrombosis is clinically ‘silent’ with no obvious signs or symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of PICC thrombosis

If there is a clot within the vein, blood flow is reduced. Therefore the signs and symptoms reflect this. They include:

- Pain and redness (erythema)

– Arm

– Shoulder

– Neck, chest or jaw

- Oedema

- Superficial vein distension

Actions

Action one: Consider measuring a baseline (on insertion) circumference of the arm with PICC insitu. Measure this at regular intervals so that early signs of swelling is noted.

Action two: Superficial vein thrombosis can be resolved with treatments such as warm compresses and anti – inflammatory medications (Wall et al., 2016).

Action three: Duplex ultrasound can be used to confirm CRT if patency is not restored with simple measures.

Action four: Deep vein thrombosis. Therapeutic dose low molecular weight heparin (LWMH) should be administered as per hospital policy or as prescribed by pharmacist or medical team.

Action five: Do not remove the PICC if:

- It is still required

- It is still fully functioning

- It is positioned adequately

- It is not infected

Action six: Remove the PICC if:

- Any of the above points are not met

- Anticoagulation is contraindicated

- If the thrombosis is life or limb threatening

- If symptoms do not appear to be resolving

Phlebitis

Phlebitis is a condition of inflammation of the vein.

Signs of phlebitis

- Pain

- Redness

- Discomfort

- Swelling

- Palpable venous cord

Types of phlebitis

Phlebitis is defined as being either:

- Mechanical

- Chemical

- Infectious

If phlebitis is suspected, the possible aetiology should be determined.

Early post insertion phlebitis will be seen as erythema around the insertion site. This is quite common in the first 72 hours post insertion, but seem more commonly if the PICC has been inserted at an area of flexion such as the antecubital fossa.

Chemical Phlebitis: Caused by irritation of the vein intima by medications that are irritant or vesicant. These include medications such as:

- Erythromycin

- Tetracycline

- Vancomycin

- Potassium

Actions for mechanical and chemical phlebitis

Action one: Apply warm compress

Action two: Elevate the affected arm

Action three: Monitor the Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) score at regular intervals

Action four: Administer analgesia and / or anti-inflammatories as prescribed

Bacterial phlebitis

This is usually associated with infection at the insertion site.

A sign of bacterial phlebitis is purulent discharge from insertion site

Actions (as above plus)

Action one: It might be necessary to remove the PICC

Action two: Obtain a culture from catheter tip and from the discharge

Action three: Monitor patient for signs or systemic infection (Liu et al., 2009)

Infection

PICC infections can be:

- Site / local

- Systemic / blood stream

- Tunnel

Signs of site infection

- Redness

- Pain or tenderness

- Swelling

- Discharge from insertion site

- Pyrexia

- Redness tracking along the vein

- If the PICC has been tunnelled there might be redness tracking along the tunnel

Actions

Action one: Obtain a swab of the entry site / discharge and send for investigation

Action two: Observe site on a regular basis

Action three: Observe patient for signs of systemic infection

Systemic / Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection (CLABSI)

According to Gorski et al. (2021), a CLABSI is diagnosed when the same organism is isolated from a blood culture and the tip culture, and the quality of organisms isolated from the tip is greater than 15 colony forming units (CFUs). Then again, differential time to positivity (DTP) requires the identical organism to be isolated from a peripheral vein and a blood culture from the catheter lumen, with growth discovered two hours sooner, for example, two hours less incubation, in the sample taken from the catheter.

Symptoms of CLABSI include:

- A history of site or tunnel infection

- Fever

- Malaise

- Back pain

- Vomiting

- Shivers or rigors usually after flushing

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension or hypotension

Actions

Action one: Closely monitor the patient and their vital signs

Action two: Obtain relevant blood cultures

Action three: Do not remove the PICC if there is only a suspicion of CLABSI. Instead, attempt catheter salvage.

Action four: The PICC should be removed if there is no clinical indication for it or if there is persistent or relapsing bacteraemia. This should be a collaborative decision and should involve a microbiologist.

Action five: The catheter tip should be sent for culture

Action six: Antibiotics should be administered as prescribed

Catheter movement

The PICC should be measured at each dressing change. If the device lengthens, this should be investigated prior to use. This is to ensure that the tip of the PICC remains in the SCV / right atrium.

Actions

Action one: Do not be tempted to reinsert the PICC

Action two: Stop any medications

Action three: Note the amount that the device has been withdrawn

Action four: Refer patient for a chest x ray to check tip position

Action five: Refer patient back to the inserter to determine if the catheter remains in an adequate position or if it needs to be removed and reinserted.

Catheter damage and Air embolism

Leakage of fluids under the dressing

Catheter damage should be suspected if there is a leakage under the dressing. Steps should be taken to investigate any leakage and to take appropriate action as soon as possible.

If a catheter gets fractured or damaged there is a serious risk of air embolism. Air in the line can cause an air embolism, a potentially serious condition. However, it takes a large amount of air (50 ml or more) to cause problems. The most common symptoms of an air embolism are a sudden onset of breathlessness, nausea, and shoulder or chest pain. Air embolism is usually a self – limiting condition and symptoms tend to subside within minutes.

Actions

Action one: If the catheter splits or becomes damaged, clamp above damage, stop medication.

Action two: If air embolism is suspected, position the patient in the left-lateral decubitus position (Durant position). Ensure patient is laying down with the heart lower than the head, lie the patient on the left hand side and administer oxygen 100% and monitor vital signs. Get emergency help as soon as possible.

Action three: If the air embolism is large and the symptoms persistent, this would necessitate mechanical ventilation and haemodynamic support to bridge over the acute event (Moon, 2003).

Conclusion

Despite best care and maintenance, PICCs are still associated with complications. Having knowledge of how to deal with them should prevent them from getting worse and should hopefully enhance the outcomes for patients.

References

-

Ast D, Ast T. Non – thrombotic complications related to central vascular access devices. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2014;37(5):349-358.

-

Broadhurst, D; Cernusca C., Cook, C., Hill, J., Naayer, K., Paquet, F. Raynak, F. (2020) CVAA Occlusion Management Guideline for Central Venous Access Devices (CVADs) 2019 Second Edition. Available online: Accessed 24th August 2022. _LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=DQsONXjChcQ%3d&portalid=0&language=en-CA.pdf (gavecelt.it)

-

Denton, A. (2016) ‘Standards for infusion therapy’, Royal College of Nursing, p. 41 t/m 42. doi: 005 704.

-

Gorski, L. A. et al. (2021) ‘Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, 8th Edition’, Journal of Infusion Nursing. doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.

-

Grau D, Clarivet B, Lotthé A, Bommart S, Parer S. Complications with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) used in hospitalized patients and outpatients: a prospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017 Jan 28;6:18. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0161-0. PMID: 28149507; PMCID: PMC5273851.

-

Liu H, Han T, Zheng Y, Tong X, Piao M, Zhang H. Analysis of complication rates and reasons for nonelective removal of PICCs in neonatal intensive care unit preterm infants. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2009;32(6):336-340.

-

Moon RE (2003) Air or Gas Embolism. Hyperbaric Oxygen Committee Report: 5–10. http://tinyurl.com/q97ywt2

-

Ullman AJ, Condon P, Edwards R, et al. Prevention of occlusion of central lines for children with cancer: an implementation study [published online ahead of print Aug 17, 2020]. Journal of Paediatric Child Health. 2020;10.1111/jpc.15067. doi:10.1111/jpc.15067

-

Wall C, Moore J, Thachil J. Catheter-related thrombosis: A practical approach. Journal of Intensive Care Society. 2016 May;17(2):160-167. doi: 10.1177/1751143715618683. Epub 2015 Dec 3. PMID: 28979481; PMCID: PMC5606399.

-

Zheng LY, Xue H, Yuan H, Liu S, Zhang XY. Efficacy of management for obstruction caused by precipitated medication or lipids in central venous access devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Vascular Access. 2019;20(6):583-591.

- Tags:

- best practice

- PICC